.do

+ .tigers

+ .melt

+ .like

+ .butter

+ .in

+ .the

+ .forest + .?

2025

Generative browser-based art

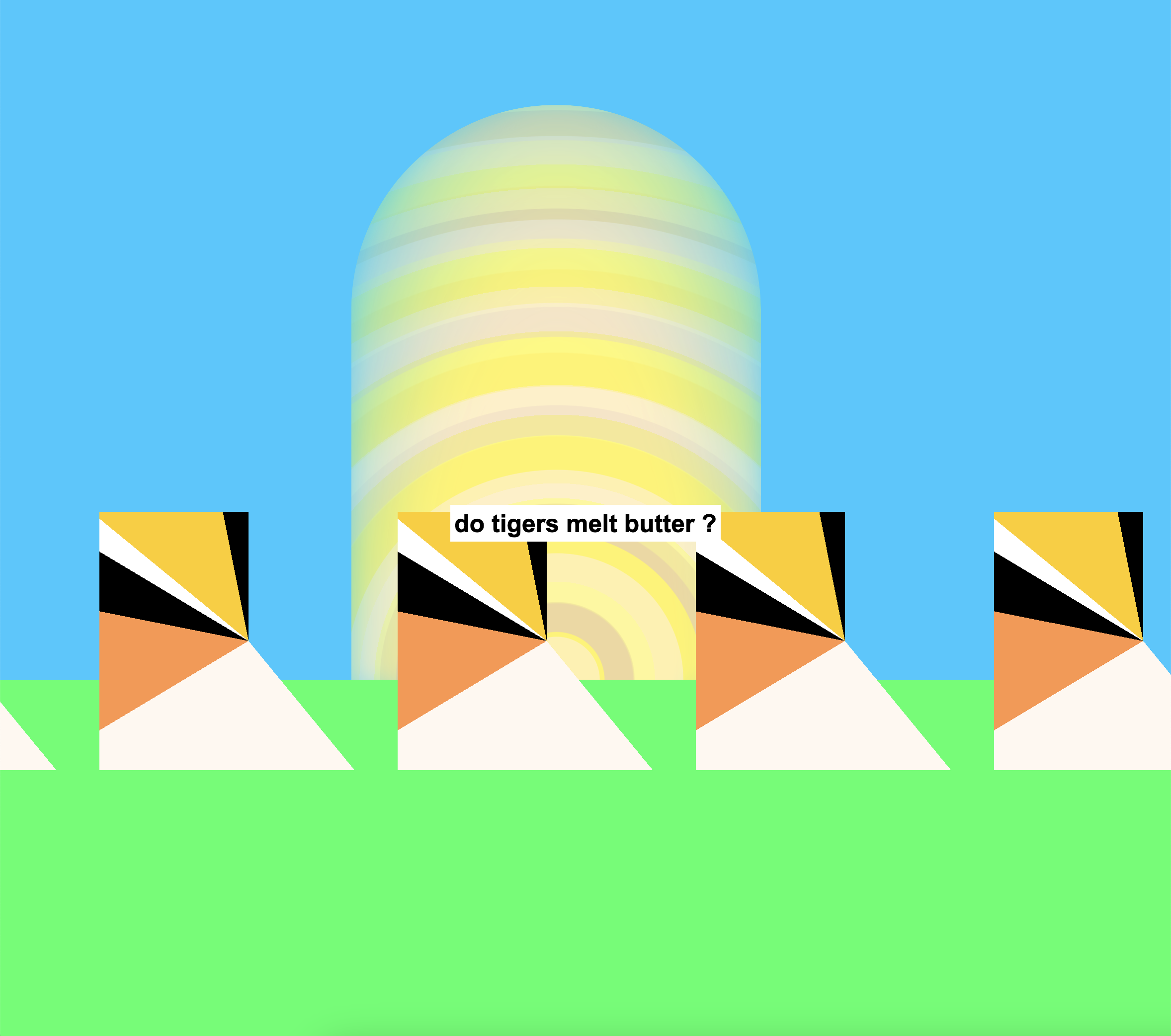

Using browser interaction and CSS responsiveness as a technical interface, this generative storybook plays with how the structure of a sentence continuously shifts. It revolves around a single nine-word sentence ‘do tigers melt like butter in the forest?’ that keeps reshaping itself in the browser.

As the reader resize the window, words disappear, reappear and reorder, and form fragments that look almost like a sentence without fully making sense most of the time.

CSS then responds to these fragments, styles them as if they made sense. In this system, CSS rules act almost like grammar. For example, the next sibling combinator “+” enforces left-to-right reading order, so even when words are randomly removed or reordered, the fragments still resemble a sentence and outputs the corresponding visual. This creates a kind of semantic pareidolia: the urge to read meaning into structure, even when none is really there.

"Do tigers melt like butter in the forest?"

This question looks like a sentence, sounds like one, and structurally, it is one. It doesn’t actually appear in the storybook The Story of Little Black Sambo, but it could have. Its peculiar logic could fit in the story.

The book, first published in 1899, has long been criticized for its racist illustrations and character names, still it continued to maintain some popularity in countries like South Korea and Japan until recently. Over time, various publishing houses released new editions, and some of them attempted to sanitize its racist implications. But the core story remained unchanged.

The story goes like this:

A young Indian boy named Sambo goes for a walk through the forest. There he encounters several tigers. Instead of eating him, each tiger take turns robbing him of his clothes, shoes and umbrella in exchange for sparing his life. Eventually, Sambo has nothing left to give. But just as he faces the risk of getting eaten, the tigers get caught up by their own greed and start arguing over who looks the most impressive, and the argument escalates as they fight over what they already took from Sambo. In this frenzy, the tigers chase each other around a tree so fast that they eventually melt into a pool of butter. Later Sambo collects the butter, brings it home, and his mother uses it to make pancakes for dinner. He eats a lot of them.

Keeping in mind that this story was written in late 19th century by an author writing from colonial India, the interesting thing about the story is how it resolves the tigers’ greed. Their greed can be read as a logic of colonial exploitation rather than a natural instinct of wild beasts: a restless need to take more, to look more impressive.

Their greed doesn’t get resolved through punishment or control. The tigers don’t get tamed or conquered in repercussion. But instead they self-destruct. They get so caught up by their compulsion to possess, that they chase themselves into oblivion and literally melt into butter. So the story stages a collapse of this greed but in a self-contained way. No one fights back and there’s no need for external force of reason to step in. The chaos just eats itself. The problem resolves itself. Then what remains after is something blameless, something palatable and something digestible. It almost looks like an imperial fantasy feeding on itself, a system that creates its own problem only to resolve it in a way that justifies why it was needed in the first place.

Because Sambo’s survival is not an act of defiance, he simply becomes a part of the cycle. He doesn’t defeat the tigers who violated him, he consumes them. But this consumption is not Sambo’s empowerment or victory, it seems closer to the system’s own reassembly, allowing it to function again. Another group of tigers might as well appear to do the same, and Sambo will once again eat pancakes made from their butter.

Therefore the question, do tigers melt like butter in the forest?, marks the spot where the narrative’s self-perpetuating logic becomes visible. Of course tigers don’t melt like butter in the forest, the phrase sounds like a nonsensical riddle that is detached from reality. But within the context of the story, it’s not something to be questioned. The transformation of the tigers into a pool of butter is framed in a way that suggests inevitability, a natural conclusion that appears to require no explanation. Just like the sentence “do tigers melt like butter in the forest?”, it doesn’t make sense, but it’s made to look like it is.

When the question is pulled from the story and placed in an open space, it reveals what the narrative is doing. Why did the tigers have to melt like butter in the forest? What does it mean for the projection of power, of threat, of restless greed, to dissolve into something blameless, something consumable?

And why does the narrative present this as a natural resolution? Do tigers really melt like butter in the forest? Maybe they do. But maybe the real question is why they are allowed to.

Various editions of the original book that circulated in Japan and Korea

Early playtest with post-its

Generative storybook first presented

@Xpub Declaration, Varia, Rotterdam, 24 Mar 2025